Water challenges are embedded in a political and ecological context, a fact often underestimated in our technocratic institutions and societies. But this is slowly changing.

In the Mekong Delta of Vietnam, Charles Howie has studied both the effects of salt intrusion on rice crops, as well as the central role played by power relations between farmers and the state in water management. This desire to understand and include the political and ecological environment which surround water discourses follows him to this day.

Through a short biography and six poems from his series Smell of Dawn – which take us on a journey through the places he's worked throughout his career – Charles allows us to delve into his life and how he arrived at this crossroads of political ecology.

"These pieces of 'free verse' are reflections on my life in different places, located in different parts of the world, since the early 1960s. It is only now, looking back, that I can see how several quite different kinds of actions have knitted together to get me to where I am, the curve of my life in the past 60 plus years."

Charles Howie

Introduction

Charles was born on the Shetland Islands in the northernmost part of Britain, in 1941. He describes himself as an 'inadvertent traveller', a reference to his parents' decision to leave post-war Britain in 1949 and go to Uganda, in East Africa. It was here that his Aberdeen-born father continued his career as a telephone engineer, a decision Charles played no part in making, but which has shaped his life and that of his siblings ever since.

"Politics in the wider sense, and ecology, have run like oxygen bearing arteries throughout my life. From growing up in Uganda Protectorate where my father was a Colonial Civil Servant, to spending 3 years employed as a meteorological assistant, a 'met. man', and biologist with the British Antarctic Survey, and finally as a British Council officer in East Pakistan in the troubled days of 1970-71, just prior to that country's tumultuous metamorphosis into Bangladesh."

After attending primary school in Kampala, Charles attended high school in Nairobi, Kenya. Here, the natural world began to collide with that of politics. He and his pals hitch-hiked to Kilimanjaro, Africa's highest mountain, climbing to the top twice, a measure of how much freedom they saw as 'normal'. There was plenty of room to explore nature, as well as work within it, while he spent school holidays working on a farm in Western Kenya.

On leaving school, he worked as a student teacher at a high school in Soroti, Northern Uganda, where he discovered his passion for teaching. He went on to qualify as a teacher of biology in 1963, but not ready to lose his freedom to the daily toil of the classroom just yet, he resumed travelling which he writes more about in his poems. After eight years however, the classroom called him back.

"After 27 years teaching biology and developing mentoring for teacher education in Scotland, I made a body swerve and enrolled for a master's degree in agricultural systems at the Royal Agricultural University in 1998. Not only did I thoroughly enjoy being a student, but I grasped eagerly at the opportunity presented to change my direction towards rice and Eastern Asia."

In July 1999, this led Charles to travel to Can Tho University, Vietnam for his field studies. At that time this was the only university in the Mekong Delta, a place with a population of 18 million. Here he wanted to learn about rice and its intolerance to salt, and the challenges farmers faced in the coastal fringe of the delta due to this.

"Meeting people is one of the greatest rewards of travelling, and in Can Tho I met Dr Vo-Tong Xuan. He was and still is referred to publicly in Vietnam as 'Dr Rice', a most warm hearted and enthusiastic man of my own age who kindly gave me 20 minutes of his time, early one morning. Afterwards I wanted to go back to this subject, to find out for myself how farming 'worked' in this vast flood plain, given its political and economic history."

Soon after, Dr Xuan invited Charles to lead a team of young teachers to develop Vietnam's first degree course in Rural Development, at the brand new An Giang University. This was the delta's second university, in which Dr Xuan had just been appointed rector. In exchange for Charles' help with curricula and staff development, they would assist him in doing fieldwork for his doctorate in political ecology.

"That was the beginning of 15 years of travel and study, and many warm and on-going friendships, in Long Xuyen City, located on the bank of a branch of the mighty Mekong River, where sometimes a cubic kilometre of water flows past each day."

In 2011 Charles gained his PhD in political ecology from London University, based on his study of the power relationship between farmers and the state in the control of water in a district in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Today, Charles lives on the edge of the estuary of the River Forth, just outside Edinburgh, from where he still sometimes ventures to work for farmers in Malawi, he's exploring how making art 'works' for him, and still teaches, this time to postgraduate students living afar.

"I have chosen dawn, my first daily interaction with the world, as a link between my many, apparently disparate, unconnected experiences. Dawn is the time I am most conscious of the extra-ordinariness of wherever I am located. This format is like a sketch book, an attempt to capture as much information, and sometimes emotions, as possible, in a compressed form, perhaps these scenes will be expanded, unpacked, and a fuller narrative will emerge later, and this is merely a first draft. Over the longer term, discontinuity on the surface, as in my life, may offer deeper fulfilment than superficial continuity. The next lines contextualise the verses that follow."

The Smell of dawn: six scenes, 1965-2019, written by Charles Howie

Signy Island

Antarctica

Signy Island is a small, triangular shaped island, approximately 3 miles by 5, located in the South Orkney Islands. The British Antarctic Survey has had a research base there since the late 1940s, and I spent 13 months there in 1965 as a 'met man' and part time biologist.

Although it lies only 20 minutes of latitude further south of the equator than Lerwick, the town of my birth, Signy has an icecap, and for several months in the southern winter it is ice bound, connected by sea ice to the Antarctic continent which is 1,500 miles to the south.

The Shetland Islands on the other hand enjoy a temperate maritime climate year-round, wet and windy but rarely freezing up, this is the benefit of lying in the path of the warmer waters of the Gulf Stream current, rather than to the south of the Antarctic Convergence.

Signy Island (October 1965)

Fetid, sharp, pungent smells await outside my tent,

Penguin poo, pink and white, squirted out, stains the rocks.

Penguins huddle in the freeze: Gentoo, Chinstrap and a few Macaroni,

Shags alight, bow to their mates, exhale deeply fishy breathes, all with such elegance.

A Leopard seal hunts across the bay below,

The penguins try to fly, but fail,

The hunter grasps one, flicks the body free of its feathered skin; breakfast for him,

Tea, porridge, tinned bacon and sledging biscuits; breakfast for me.

Dacca

Bangladesh

Dacca, now Dhaka, the capital city of East Pakistan. In March 1971 a civil war broke out, with Bengali people fighting the Pakistani army to be independent, which they achieved in December of that year.

I was an employee of the British Council during the preceding 18 months, focused on science and science education, but I left the city a few days after the fighting began. On my way back from my first visit to Vietnam in August 1999, I returned to Pakistan, a country which now seemed more at peace with itself; next year Bangladesh will celebrate its 50th birthday, I'm excited about that.

Dacca, East Pakistan/ Bangladesh (February 1971)

Dawn is heavy with the smell of spices-fenugreek (?) and the fumes of 'baby taxis'.

Muezzin summon the faithful before dawn, all wake, but only some pray.

Dogs bark, a dog and a cow argue over rubbish piled at my gate.

"Bed tea memsahib, bed tea sahib?"

Newly cut papaya with squeezed lime precede fried eggs; no bacon in a Muslim country.

Outside, the roads are crowded, people jostle along, unaware of revolution, bloodshed, and death just ahead.

Mekong delta

Vietnam

The Mekong Delta, in Vietnam, is the rice bowl of Vietnam and beyond. In July 1999, while studying at the Royal Agricultral College, now a university, in Cirencester, England, I was fortunate to win a travel scholarship from the Arkelton Trust. This enabled me to visit Can Tho University for two weeks, to learn about rice growing and the problems of saline intrusion, in Soc Trang Province. I was invited and hosted by Professor Vo-Tong Xuan, Director of the Mekong Delta Farming Systems Research and Development Centre. It was the first step in a long relationship, which now spans aquaculture, organic agriculture, and the social sciences.

Can Tho City, Vietnam (July 1999)

Before dawn loud speakers on lamp posts announce the Good News from Party HQ.

The smell of dawn is sharper here, acrid, laden with scents of charring meats, cooking on open braziers.

Ceaseless rain, flooded roads, calf deep sometimes, feet always wet, but warm, bilharzia? I hope not.

Cold rice, grilled pork, pickled vegetables and a fried egg my breakfast.

Each day new smells, sights and sounds, best abandon all comparisons to old normalities.

Manzini

Swaziland

Swaziland is a kingdom surrounded by the Republic of South Africa on three sides, and Mozambique on the fourth. My friend Boyie Dlamini, who I'd met when studying agriculture in Cirencester, invited me to visit his hometown of Luve, about 25 km northeast of Manzini, to help his community take an idea for a water reservoir forward. This was my first return to Africa since I'd left in 1960, the welcome was very warm and quite an emotional experience.

Manzini, Swaziland (April 2004)

The air is humid, dense, lying as a cloudy mat on the damp grass.

Smells flow past my nose: peaty fires, fresh cut grass and burning wood.

Voices come through, soft, not sharp, from left, from right.

The smell is clean, with cattle, peat fires and the aroma of freshly dug soil.

In the grass beside me a giant snail slithers past; to eat, or to be eaten?

Mekong delta

Vietnam

The Mekong Delta, in Vietnam, then called me back. After completing my MSc degree, I sent a copy of my dissertation to Dr Xuan and asked if I could return. We agreed that if I assisted with curriculum and staff development, he would provide me with access to all aspects of agriculture for my research.

In 2013, after completing my doctorate, I made my ninth and most recent residence at An Giang University, this time working on a revision of the crop science curriculum. By the end of that time, I had helped the university write two curricula, I had trained and mentored many staff, and I had earned my doctorate in political ecology from Royal Holloway, University of London.

I also had, and still have, a new and ever-expanding family of friends, in the Mekong Delta, and beyond. Staff who started with me in 2001 now have permanent positions in universities in the USA and Australia, are deans and heads of university departments, and one has an international business in education. I could not say I foresaw any of that, back in 2001, when I first arrived at the fledgling An Giang University. At that time it was a teacher training college, with just tens of university students, it now has around 10,000 students.

Long Xuyen City, Vietnam (spring 2013)

Morning jog and stretching exercises on the Guest House roof, at 6am.

For many the day opened at 5, or earlier: a run; Tai Chi exercises; a game of badminton.

The smell of cooking meats, the sounds of flying ducks, the roar of motorcycles.

Over the wall a farmer's stately Muscovy ducks ponderously lift off, fly 50 yards and settle on ancestors' tombs; tails wag, settling noises, duty done, day fully underway.

Salima

Malawi

Malawi; after Vietnam. The thought of what comes next troubled me as I left Vietnam in 2013. After working on teacher education back in Can Tho University, where my Vietnam life had begun long ago, was I finally going home to retire? – which also begged the question where was home? One Vietnamese friend had warned me, in my first weeks in 2001, 'be careful Charles, the Vietnamese will use and abuse you for all you know', to which I had replied, 'if you keep feeding me you can have all I know', and so it has proved.

I still edit and referee journal articles, write supporting letters for grant applications, and keep up with the lives of those who started with me back in 2001 – they are married with children going to high school now. Many of them include me in tales of their travels, research, births, marriages, deaths, and holidays. At home, I even make sour soup with slices of catfish to remind myself of the wonderful foods of the Mekong Delta.

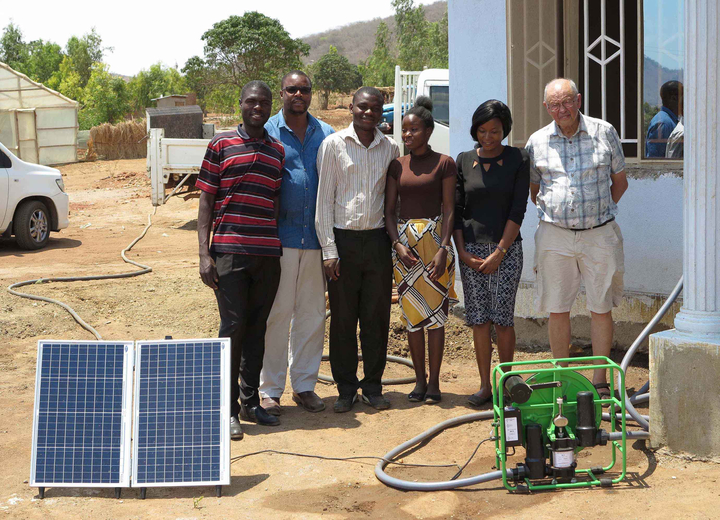

However, just when I thought I was winding down, in my mid-70s, I had a chance conversation in a church in Argyll, Western Scotland. This led to a meeting with the trustees of a Scottish charity a few days later, working to improve the lives of farmers in Northern Malawi. They were Christian businessmen, their lives rooted in Scotland, some of them extremely successful, trying to nurture agriculture as a business concept among small scale subsistence farmers in the middle of Africa, whereas I had been a wanderer, a teacher, an academic researcher, with knowledge of rural life and agriculture.

Taken together we had a sort of complementarity, and I'm now the technical adviser to Malawi Fruits, using all the skills and knowledge accumulated over decades. Once again, I am at the nexus of politics, ecology, and economics and I feel at home. I've been to Malawi twice; the final verses are a reflection on experiences from my second visit, in 2019.

Salima and Mzuzu, Malawi (2019)

Malawi dawn, Africa style, soft noises, soft smells, from very early on.

The overhanging Baobab tree has seen 292,000 dawns, or so they say,

But now climate change may wipe it away, or so they say.

By dawn the fishermen's harvests from mighty Lake Malawi are nearly sold,

Only glittering mounds of tiny silver fish remain, reflecting the dawn like shards of glass

Inland, further north, in elevated Mzuzu, dawn begins with the muezzin's call,

Next, benign water noises sound as the night watchman waters Atusaye's tomato trials,

Soon, the smell of freshly made coffee will fill our house, and our day will begin,

Can solar powered water pumps and salad crops grown inside polythene-covered tunnels improve livelihoods?

Underlying all we do lies population growth, climate change, and the never predictable power of nature